Artificial Intelligence in 2026

Reflections, Predictions, and Some Wild Speculation

At the outset of 2025, for many people, generative artificial intelligence meant one thing: a chatbot. Specifically, OpenAI’s ChatGPT—an advanced but sometimes unreliable heir to Google Search. Progress was measured by the increasingly clever questions we tried to stump it with, a game that produced equal parts magic and equal parts slop. That era is gone.

As the year comes to an end, the chatbot has reached maturity. In most use cases, it gives an accurate response—free from the misunderstandings, biases, and hallucinations that once characterised it. Progress has moved on to other frontiers: coding and the construction of complex systems that act as AI agents.

What once amazed us, we now take for granted. For my entire life, computers have solved difficult problems—including complex mathematical calculations. Now, that includes problems from the International Mathematical Olympiad. So what? When we Google, an AI response appears before we can click through to Wikipedia. We have all become AI users. And precisely because of the familiarity, we perceive it as a plateau—and if AI progress is plateauing, surely that means we’re in an AI bubble, right?

Welcome to the Senior Decision Maker’s third annual analysis of the year in AI—written for business leaders on the front line of progress, who aim to stay a step ahead of what mainstream media channels can offer. As usual, I’ll reflect on the year behind us and the year ahead, with five bold predictions for 2026—and one prediction of what we won’t see. New this year is that AI will evaluate and rate my predictions from last year. It led to some drama and nearly had me rage-cancel my OpenAI subscription. That aside, I kept my streak of being more right than wrong, and you can compare it with previous editions here:

The Year of Vibe Coding and Agents

The term “vibe coding” didn’t exist a year ago, and it may not survive a year from now. Yet it encapsulated 2025. Coined by Dr Andrej Karpathy in February, it means coding without writing any code yourself—letting an AI write the code according to your instructions. Even your elderly relative, while struggling to master the TV remote, can now produce code that would have won competitions a year ago.

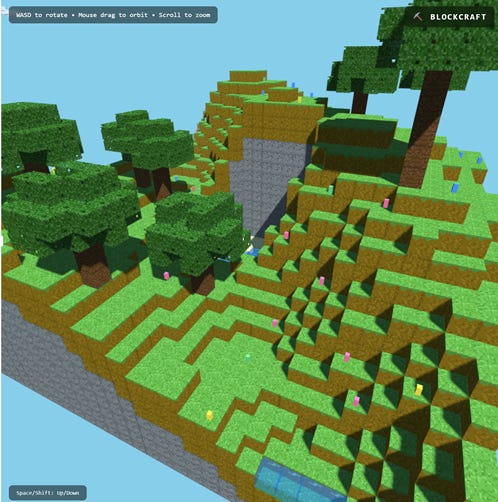

When I ran corporate AI training in early 2025, participants were assigned to code a simple snake game—the one made famous by the Nokia 6110 back in 1997—from a single-sentence prompt. Now, at year’s end, we can do much more advanced things, just as easily. I built this interactive Minecraft island from a single sentence using Claude Opus 4.5 – the result appeared directly in the chatbot window.

This opens a question: what can you do when writing code becomes trivially easy and fast? Could you build features—even entire applications—just-in-time, as you need them? Do you really need all those SaaS subscriptions, or can you build the applications yourself?

Incorporating employees’ home-tinkered applications quickly and easily into a complex and well-guarded corporate IT environment remains science fiction. But all they need is their own smartphone, and they can get it done today. For IT Security, it is the worst nightmare.

It gets worse. With access to enough compute, it becomes possible to replicate a competitor’s entire codebase, built from the ground up with a modern architecture, without the legacy and bugs. After that, all that is needed is to add a few visible improvements, dump the prices, and launch a marketing campaign. Elon Musk grasped this and started the company Macrohard.

If Microsoft—the world’s fourth-largest company by market cap—is susceptible to this, smaller companies should worry. It won’t happen tomorrow. Yet for many, this threat remains entirely off the radar.

What companies have on the radar, though, are AI agents that can perform the work of employees. I have been writing about them since early 2023. At that time, their performance was miserable, and they were good for nothing. That has gradually changed, not just because the AI models have become smarter. They have become better at using tools.

But for an AI to use a tool, it needs an interface to access it. Enter the Model Context Protocol (MCP)—think of it as a universal USB-C connector for AI. It’s an open standard for how AIs communicate with tools, systems, and data sources, bridging the gap between the model and the world outside. It does so in a general, flexible way, unlike traditional application-to-application connections (APIs), which require custom integration for each connection. Anthropic developed MCP in November 2024, and surprisingly, the industry adopted it quickly without fracturing into competing standards. The results are starting to emerge. AI agents today can create documents, send emails and messages, and trigger workflows in enterprise systems like SAP and Workday.

AI agents exist on a spectrum. At one end, something that looks like the usual chat interface; at the other, a virtual employee running in the cloud. As of 2025, the complex end of the spectrum is still a challenge. Partly due to limitations in the models themselves—tool use, memory, continuous learning—and partly due to the scaffolding needed to turn a model into an agent. We are still in the early innings here.

To see the potential, we have to look toward the simpler end. Consider OpenAI’s Deep Research; it wasn’t the first agent to search the web and compile a report—I wrote about Gemini’s Deep Research last year—but when it arrived in February 2025, its performance made it a game-changer. I would estimate that the output you can get in 15 to 20 minutes is equivalent to a report from two junior management consultants working for a month at a cost of around €50k. An excellent senior consultant might produce something more profound, but the AI report would likely be clearer, better written, and contain fewer errors. Management consulting will never be the same. And as the saying in AI goes: this is the worst these systems will ever be.

The Year of New Frontier Models

OpenAI’s Deep Research was based on the o3 line of thinking models, but it wasn’t the big new model we had been waiting for since GPT-4 launched in March 2023. In last year’s review, we noted that large new frontier models were notably absent in 2024. Surely, 2025 would deliver.

For OpenAI, it almost didn’t. I wrote about this in my article “Artificial General Intelligence.” The short story: building frontier models has become increasingly challenging. OpenAI stumbled, losing the advantage that was their raison d’être. They responded by declaring “Code Red.” The media interpreted this as an internal initiative to regain leadership. I suspect, however, that it was a marketing campaign—designed to generate maximum attention for the model they were about to release.

That model, reportedly codenamed “Garlic” (an antidote, perhaps, to the Gemini vampire draining OpenAI’s growth), was already complete. Larger, thinking longer, and therefore more expensive to run—OpenAI may have hoped to keep it in reserve, saving compute for development of the next generation of models. But competitive pressure forced their hand. The December 11 release, GPT-5.2, finally delivered the leap we had expected from GPT-5 a year earlier.

Other AI labs fared even worse. Anthropic also struggled with their new models; they couldn’t match the frontier leaders. They were, however, exceptionally good at writing code. Anthropic pivoted, focusing on coding and agentic use cases, targeting enterprise customers. So far, it looks like a successful move.

Meta fared the worst of all. The Llama 4 series, released in April 2025, fell far short of expectations. Panic followed. The largest model, Llama 4 Behemoth, was postponed indefinitely. With that, I think we can exclude Meta from the frontier race. If you’re aiming for the top, you need at least a trillion dollars in commitments over the coming years just to get a seat at the table—and even then, you must top the benchmarks in at least some categories when new models drop. Meta couldn’t. I expect they’ll eventually attempt a comeback from a different angle, but we can count them out for now.

Meta’s demise opened the door for Chinese players in open-source AI. DeepSeek had a moment when they released R1 in January 2025—a surprisingly capable thinking model, far more efficient and therefore cheaper than the frontier alternatives. But DeepSeek was not alone. Alibaba impressed with their Qwen models, Moonshot AI with Kimi K2, Z.ai with GLM-4.6, and MiniMax with M2.

However, China isn’t the only source of strong open-source models. The European company Mistral can match the best—without the political baggage. You may not have heard much about them; they favour a low-key marketing strategy, and their success doesn’t fit the dominant narrative: a two-way race between American frontier labs and Chinese open-source challengers. In that narrative, Europe is irrelevant. It is a narrative which doesn’t quite match the facts.

This leaves us with the 2025 winner in the AI model race: Gemini from Google DeepMind. In a way, this was a surprise. As recently as 2024, they were the laughingstock. Then, their notoriously over-tuned model insisted on political correctness to the point of absurdity, generating historical images of Vikings and German WW2 soldiers depicted as Afro-Americans or Asians.

But Google had both the knowledge and the resources to do better—they invented generative AI back in 2017, with the transformer architecture. The turnaround came when they combined their research and product development units under the leadership of Demis Hassabis. Such reorganisations are rarely frictionless; still, results soon followed. In last year’s report, I noted that Google was the first lab to release a next-generation model: Gemini 2.0. It was quickly followed by 2.5, then the autumn release of Gemini 3.

As is often the case in AI, that model didn’t stay on top of the benchmarks for long—Anthropic countered with Claude Opus 4.5, and OpenAI with GPT-5.2—but Google had clearly cracked challenges that others had not. They appear to have an edge in multimodality: combining text, code, images, and video more seamlessly than competitors. That could prove decisive.

Another factor is that Google can use its own hardware. Their Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) are purpose-built for neural network training, unlike the general-purpose GPUs from NVIDIA that everyone else relies on. With all components in-house, they can also optimise the entire training pipeline end-to-end.

Finally, there’s the dark horse: Elon Musk’s xAI, a start-up lab that has also acquired X (formerly Twitter). As is often the case with Musk ventures, they’re betting everything on a future scientific breakthrough that would give them a monopoly-like position. Their models have impressed, briefly topping benchmarks in some areas. But they’ve also made strange choices—deliberately tuning the model to favour Musk’s views and those of the current US administration, and prioritising companion bots, with adult content.

Compared to other AI labs, xAI faces a revenue challenge. While OpenAI has a revenue run rate approaching $20 billion, xAI has only a fraction of that. And that revenue comes primarily from advertising on X, which has been declining steeply in recent years. It’s hard to see where paying users will come from without a breakthrough that makes their offering unique. For now, investors keep pouring in money. That works—until it doesn’t.

AGI and the Missing Piece of the Puzzle

The technological breakthrough that all the leading labs are chasing is AGI. Two years ago, I guessed that OpenAI would declare they had crossed the AGI threshold within 12–18 months, which aligned with my expectations for the GPT-5 release. I was wrong. What was supposed to be the AGI-level model, after many delays, got released as GPT-4.5—and it wasn’t even close to the frontier. Despite this, I wrote in the article “Artificial General Intelligence” that we have now largely met the criteria for AGI. Yet something is missing. No one can pinpoint exactly what.

To understand the big picture, we can zoom out. Humans have always been inherently lazy—we prefer that someone else do things for us. Over time, we realised that technology could be that “someone else.” The quest to build technology that could do what humans do, both body and mind, began tens of thousands of years ago.

We started with technology that can do what our bodies can do. We can call that artificial muscle power. It has evolved over thousands of years, from simple tools like the lever, to using animals such as oxen, to advanced machines today powered by everything from electricity to rocket fuel. Tools for the mind were initially less notable. But written language set us on an arc that led to libraries, the printing press and the scientific method. This arc took off exponentially in modern times with the advent of computers, then the internet. The next step in that evolution was AI, which gave us hope of fully replicating what the human body and mind, in unison, are capable of. The final piece of that puzzle is what we call AGI.

We are very close. Dr Alan Thompson has built a rigorous framework for tracking AGI progress; his November 2025 estimate put us at 96% of the way there. That remaining gap may be small, but it is clearly felt. Anyone who uses the models regularly can sense that something is missing. The prime candidates are memory and continuous learning.

But it’s not purely a memory issue. I would describe it this way: when I prompt an LLM, I tend to get a good answer on the first try. I can then ask it to refine and provide more context, and get something even better. If I continue this process, I expect the model—like a human would—to converge on increasingly better answers. Usually, it doesn’t. The second answer might still be the best. We’ll encounter a real-world example of this when we evaluate last year’s predictions.

I’m hopeful this will be solved relatively soon. Last year, I listed continuous learning as something that could potentially be cracked in 2025. Now we’ll see if 2026 delivers. Remember: five years ago, only a small group of researchers at a handful of labs and universities pursued this work. Today, thousands of people worldwide, backed by billions of dollars, are working to solve it.

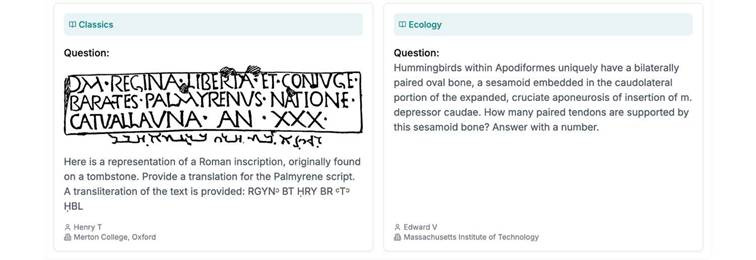

Saturating the Benchmarks and Contributing to Science

Whether or not the AGI threshold is reached, AI models have improved rapidly—so rapidly that it has become hard to measure. This led to benchmarks like “Humanity’s Last Exam.” As the name implies, the aim was to create the most challenging test humans could construct. Researchers crowdsourced questions from experts worldwide. In total, 70,000 candidate questions were collected, of which 2,500 were selected. The criterion was that the best AI models at the time should fail to solve them. Even skilled human experts would likely struggle to score above 1% on the test.

A year ago, there was a massive leap in benchmark performance: Claude 3.5 Sonnet, then the leader at 4%, was beaten by OpenAI’s o1, which achieved 8%. Now, a year later, Google’s Gemini 3 Pro is scoring 37.5%—a score that, since I wrote this a week ago, has already been beaten by OpenAI’s GPT-5 Pro at 42%. And as if that weren’t enough, as I revise this, the communications company Zoom has come out of nowhere, claiming 48%.

As benchmarks become increasingly saturated, researchers are turning to other ways of measuring models: real-world scenarios such as managing capital, running a business, playing computer games, or competing alongside humans in science competitions.

In my “Artificial General Intelligence” article, I wrote about how both OpenAI and Google achieved gold-medal performance in the International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO)—something neither domain experts nor superforecasters expected for years. I had this on my list of predictions last year, but I failed on a technicality. More about that later.

Beyond benchmarks, AI models are beginning to make meaningful contributions to science. Using AI as a tool for scientific discovery isn’t new—Demis Hassabis won the 2024 Nobel Prize for work that produced AlphaFold, now ubiquitous in medical labs worldwide. But that was a specialised tool. Now, general-purpose chatbots like OpenAI’s GPT-5 Pro are solving open problems in mathematics and other fields.

Too Big to Fail: The AI Bubble

When AI models can contribute to science, power autonomous weapons and cyberattacks, and persuade large groups to change their opinions, AI becomes a cornerstone of geopolitics. We are very close to that point. Close enough that every major actor can see it coming—and recognises the race to get there first, or risk being steamrolled by those who do. Nations would be prepared to spend almost anything to avoid that fate. Yet so far, it is not nation-states spending astronomical amounts on AI infrastructure. It is private companies.

The motivation for these companies is not purely to secure geopolitical dominance for their home countries—it is also corporate profits. And while the total pie may be enormous, its distribution is far from certain.

AI development could take several paths. In the main scenario, AI continues to improve based on technologies we already have, simply by scaling them up. Researchers are already using AI models to develop the next generation of AI models. It is reasonable to expect that, at some point, recursive self-improvement kicks in—better AI creating even better AI. If that happens, progress could accelerate dramatically. So dramatically that the first company to reach that point gains an advantage that competitors can never close. A natural monopoly. That company would, if unchecked, capture a large share of global GDP—and grow it rapidly from there.

If there is a reasonable chance of winning that position, there are virtually no limits on what a company would spend to get there. In practice, this means buying every chip available (read NVIDIA’s GPUs) and the energy to power them. The early stages of this scenario are already playing out.

The problem is that the scaling scenario is not a given; there are other probable scenarios. While most AI insiders believe in some variant of scaling, there are researchers who believe that alternatives to transformer architectures will prove more fruitful. We will come back to that.

What makes the situation even more challenging is that the infrastructure being built today is replicated in at least four near-identical copies—one for each of the major US AI labs: OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and xAI. OpenAI alone has committed to spending $1.4 trillion on infrastructure in the coming years.

In the past, it seemed like these labs were pursuing different approaches, which would make them increasingly differentiated over time. I’ve recently changed my mind on this. It now looks, to me, more like they’re betting on the same things. In a winner-takes-all scenario, three of the four would fail.

The safe bet, so far, has been NVIDIA—where most of the money ends up regardless of which scenario wins. But high expectations are already priced in, and several well-resourced players are working to break NVIDIA’s de facto monopoly on AI compute, with Google and its in-house TPUs appearing furthest along.

The trillions of dollars at risk here are not just stock-market exposure and venture capital. A large part of the buildup is financed by banks packaging AI infrastructure into investable products. This has uncomfortable parallels to the financial products created from U.S. subprime mortgages that led to the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2008. We can hope lessons were learnt. Still, it may be our money at risk once again, held by pension funds, insurance companies, and governments in ways that are not fully transparent to anyone.

None of this guarantees an AI valuation bubble. But what makes one likely—and here the economists and journalists are correct—is the volume of circular deals in the AI space. The marginal buyer of high-valued AI stocks is often another AI company, paying with its own high-valued stock in a deal that pushes both valuations higher. This is unlikely to end well, even if increasingly profitable AI adoption can delay the reckoning.

But since being part of the AI inner circle seems to guarantee higher stock prices, no company wants to be left out. Recent months have brought a wave of companies seeking entry: Nokia announced a strategic partnership with NVIDIA; Disney invested $1 billion in OpenAI, bundled with an IP usage agreement.

To put valuations in perspective, consider Thinking Machines Lab—a start-up founded in February 2025 by OpenAI’s former CTO Mira Murati. They have about 50 employees and one product, an API for fine-tuning LLMs. Its commercial value remains unproven. Yet they are targeting a capital raise at a valuation of up to $60 billion. For context, that’s roughly the combined market cap of Ericsson and Nokia—two companies that together provide a significant share of global telecom infrastructure. When someone like OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman says that markets are “overexcited about AI”, this is likely what he has in mind.

Corporations Need to Pick Up the AI Bill

High valuations of AI companies reflect an expectation of future cash flows. Consumers can account for part of that, but Web 2.0 taught us that subscriptions for internet services rarely exceed $10–20 per month in wealthier countries—and less elsewhere. Most users don’t pay at all; business models rely on advertising instead. That won’t be enough for the AI industry. Corporations will have to pay. It was no accident that Anthropic pivoted towards corporate customers during 2025, and that OpenAI marketed the GPT-5.2 release primarily as “good at doing real-world knowledge work tasks.”

The global SaaS market is currently around $300-400 billion. That’s not enough either. What AI companies need to target is the roughly $70 trillion in salaries companies pay each year. The challenge isn’t just replacing a large share of the workforce—it’s getting paid for doing so. Companies are unlikely to pay the same for a virtual AI worker as they currently pay for a human employee. More likely, AI providers will initially capture something like one-hundredth of a fully loaded salary cost. And even that won’t all flow to the AI labs.

To become an effective agent managing a specific job role, an AI likely needs tailored scaffolding. The providers of that scaffolding become middlemen—and they will take a cut. This layer of the value chain is where the differentiation that matters to corporations actually occurs, and where they’re willing to pay. We can expect the AI labs not to abandon this position in the value chain without a fight.

The raw intelligence from the AI model itself risks becoming a commodity. If several AI labs can provide solutions at a similar level, prices will drop quickly. The floor is the cost of energy used to power the chips. If free, open-source alternatives can match the leading models, that’s likely where prices end up.

We can expect this to lead to a distinction between jobs where “good enough” suffices and those where improvement is always possible. Consider someone who manages incoming invoices and ensures they get paid. They can never do better than correct. A cheap, standard model will eventually be able to handle that. Now consider an architect. There is always a better design. For that work, there’s an incentive to pay a premium for the very best AI model. For AI labs’ revenues to flourish, they had better hope most jobs fall into the second category.

For consumers, all of this means that everything with labour and information as major cost components will get cheaper and cheaper, while products dominated by raw materials will not. The flipside is that consumers will risk losing the jobs that let them afford anything at all.

The Short-Term Corporate Use Cases

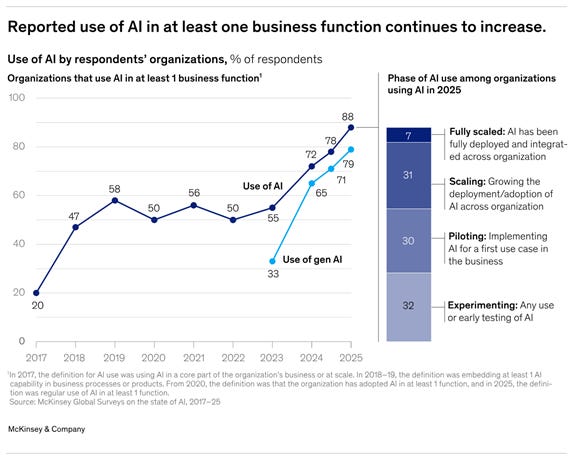

Human employees will not be replaced entirely by AI next year—these transitions take time. I have a rule of thumb: companies add about 2% to productivity each year, so it roughly doubles every 35 years. Where that 2% comes from depends on what new technology is available. Forty years ago, it was the computer; thirty years ago, the internet; twenty years ago, corporate software suites. Alongside these came new management philosophies, improved ways of working, and better goal-setting and follow-up. If my rule of thumb holds, the next wave of productivity gains should come mainly from AI. And if AI can outperform previous technologies, we might see more than 2% per year. At 5%, productivity would double in about 14 years. Are we seeing hints of that?

The short answer is no. Almost every company is now using AI to some extent. But augmentation—humans working alongside AI copilots—has not yet produced significant benefits. Not because the potential isn’t there, but because it’s hard. Workplaces are complex systems guided by both formal processes and informal ways of working. We shouldn’t expect to inject intelligence into that system, like adding nitrous oxide to a combustion engine, and have everything work better. To fully leverage AI, we need to rebuild the systems themselves.

Employees should welcome gradual, trial-and-error adoption of AI in the workplace. I’ve said before that if a company isn’t actively pursuing AI now and deliberately testing hybrid solutions, the implicit or explicit strategy is to replace employees entirely with AI as soon as possible, without wasting effort on training them or seeking alternative solutions in the meantime. Even if that strategy eventually fails, employees can still lose their jobs in the process.

Still, 2025 has seen progress in employee AI use cases. Current models are excellent at producing research reports on unfamiliar topics. It may now be more valuable to send your manager a raw CSV of the sales data than to spend hours preparing dashboards and graphs—the AI on the other end can generate whatever view they need. With Claude Opus 4.5, you can create decent PowerPoint presentations, and with some extra steps, even render them in your corporate template. All of this adds to the productivity features we already had: drafting texts and emails, taking meeting notes, planning events, and translating. From my perspective, the most underutilised use case remains decision-making—a clear area where you can achieve 10x impact with minimal investment in scaffolding or training.

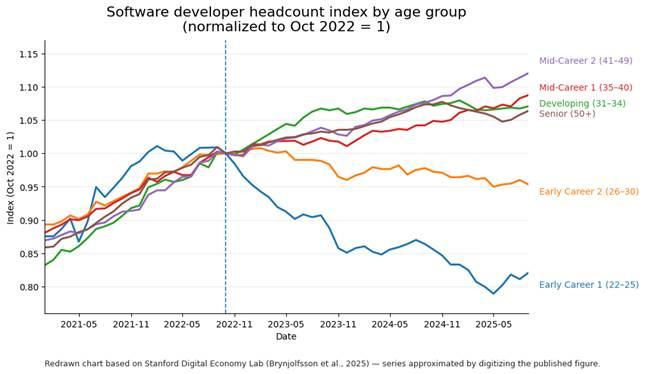

From a corporate function perspective, software development remains the strongest use case. We’re already seeing the impact on the job market. As AI performs on par with junior developers, hiring of people in their twenties has plummeted, while demand for senior developers continues to rise. As models improve, we can expect this pattern to extend to older cohorts as well.

What we’ve seen in software development will likely repeat in other functions. Customer support and interaction is one area ripe for AI agents; marketing and communications is another, where AI can generate large volumes of high-quality prototypes. Other use cases are emerging as the technology matures.

OpenAI has developed a benchmark, GDPVal, to measure how well models perform on real-world, GDP-contributing tasks. The initial version covers 44 occupations across nine industries, collectively accounting for 5% of U.S. GDP. Human graders compare AI-generated output with that of industry experts and select which they prefer. At the start of 2025, using GPT-4o, AI output was preferred 10% of the time, and human expert output, 78% (the rest were ties). With GPT-5.2 Pro, AI output is now preferred 60% of the time, while human expert output is preferred just 26% of the time. The crossover point, when AIs overtook human experts, was December 11, 2025—as of writing this, too recent for the practical effects to be visible.

Boosting individual productivity with generative AI and improving productivity within specific corporate functions are steps one and two of my AI maturity model. I won’t go deeper here, but for those interested, I updated my Corporate Generative AI Framework (version 3.0) during the autumn, which covers these mechanisms in detail.

The Era of Slop

An emerging challenge for companies is that, as producing material becomes trivially easy, the volume eventually drowns you. The problem isn’t that AI output is bad—it’s that it’s good enough that we don’t bother refining it. A report that once took a week can now be drafted in 15 minutes. If we spent that week refining the AI draft, we’d likely get something 10x better than what we used to make. Instead, we settle for the unrefined 15-minute version. We make 20 of them in a week, none of which are good enough, and no one has time to read any of them. This is how we drown in slop.

This isn’t just a corporate phenomenon—slop is flooding social media too. Over the past year, image models have become increasingly realistic and easier to control in fine detail. Video models like OpenAI’s Sora 2 and Google’s Veo 3.1 are now so good that, at first glance, you wouldn’t recognise them as AI-generated. A polished social media clip can be created in seconds. The result is that a torrent of such posts is crowding out the deliberately crafted content that once took days or weeks to produce.

I asked an AI whether this was what the “dead internet theory” meant—that the internet is now mostly AI-generated content, primarily read and commented on by other AIs. It wasn’t. The dead internet theory, Gemini informed me, is actually a conspiracy theory. The reality, it said, is that “the internet is more like a ‘zombie apocalypse’—still active but lacking its original human soul, kept alive by algorithms and attention farming.” That gave me little comfort.

But there has to be another side to this, because people seem to genuinely like their AI models.

What Do People Use AI For?

OpenAI experienced this the hard way. When they released GPT-5, they retired the legacy models, assuming users would welcome the upgrade. The backlash was massive. OpenAI was struggling with a GPT-4o that was both too sycophantic and, more troubling, accused of being complicit in suicides. They couldn’t wait to get rid of it and replace it with GPT-5, which was better in every way. It turned out the users really loved sycophancy.

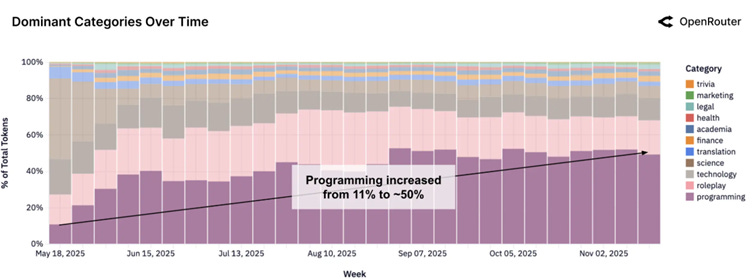

It gives some hints on how people actually use AI. However, by token volume, coding overtook all other use cases in 2025, now accounting for half of AI workloads. This is especially pronounced at Anthropic, where 60–70% of tokens are allocated to programming.

But it’s the second-largest category that explains the GPT-4o backlash: using AI as a companion, here labelled “roleplay”. The major closed-source labs all restrict companion use, though xAI is more permissive than the others. Users who want no restrictions turn to open-source models. In the Chinese model DeepSeek, 80% of token usage is classified as roleplay. I previously thought Meta would dominate the entertainment side of AI, including companions. It now looks like China is a step ahead—at least in this category.

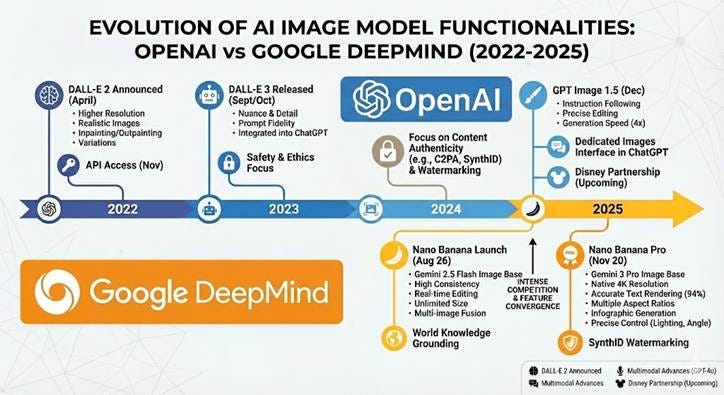

However, there’s one entertainment use case that OpenAI and Google haven’t ceded: image generation. Throughout 2025, releasing a new image model was the surest way to boost usage and app downloads. These models aren’t developed purely for entertainment. A significant purpose is enabling AI to reason visually, that is, to let it think in images and not just in text.

But entertainment drives adoption. In March, OpenAI released 4o Image Generation, which created the “Studio Ghibli moment.” The model excelled at converting any image into the style of the Japanese animation studio behind films like Spirited Away (2001). Perhaps this also revealed the age of the core user base? The reign lasted until Google topped it with Nano Banana and later Nano Banana Pro. Suddenly, everyone was making infographics.

You can also give Nano Banana Pro simple sketches—that is how I made the cover image for this article.

Revisiting My Predictions from Last Year

A Danish proverb, popularised by the physicist Niels Bohr, holds that “it is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.” The challenge here is to make predictions that are interesting and precise while still having a reasonable chance of coming true.

None of my predictions from last year were safe bets, and I may not have gotten any of them entirely right. Still, I think I captured the sentiment. I used GPT-5.1 Pro to evaluate my performance—it gave me a score of 20 out of 30. I claim I deserved 22. Either way, I’m satisfied with my accuracy. Before we head into the details of that, let’s first look at what I’ve changed my mind about since last year.

First, looking at the AI labs—OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind, and xAI—I now believe there is far less structure, planning, and strategy than I previously assumed. AI labs, particularly OpenAI, are notorious for poor product naming. I used to think that it was because they were just bad at naming things. Now I think it’s a symptom of chaotic operations. Training runs fail, initiatives run in parallel, and until the final moment, it’s unclear what will be released or under what name.

I also used to believe the labs had access to next-generation models for internal use—models too expensive to release publicly, used for synthetic data generation and reinforcement learning with AI feedback. I still think they have better models internally, but now I suspect it’s more modest: the next imminent release, early checkpoints, models that use a bit more tokens than the public versions. Not a step-change beyond what the rest of us can access.

Another thing I’ve changed my mind on is how differentiated the AI labs really are. I used to think OpenAI was betting more on multimodality and reasoning, Google DeepMind on world models, and xAI on pure scale. Now I don’t think the differences are that significant. All the main labs are doing roughly the same thing. We have at least four companies making trillion-dollar commitments over the next few years to pursue essentially the same goal, in the same way.

That doesn’t mean the labs’ work is easy. While I expected them to encounter trouble during 2025, I underestimated the scale of OpenAI’s problems. A year ago, I was optimistic. I thought their main challenges were behind them. That was not the case. GPT-5 was supposed to be a step toward AGI. Instead, the release felt more like a marketing ploy. A nothingburger for most users, except that free users gained access to decent thinking models for the first time. But as we discussed earlier, users missed their sycophantic GPT-4o and protested until they got it back.

Another thing I didn’t fully appreciate a year ago was the extent to which financial dynamics would shape AI development. The US is making a multi-trillion-dollar bet—not on AI in general, but specifically on transformer-based generative AI improved through scale (that is, more chips in data centres). It has become too big to fail. An AI collapse would likely trigger something similar to the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2008, from which Europe, at least, still hasn’t fully recovered. Financial markets are aware of this. We saw how nervous they got during the “DeepSeek moment” in early 2025, when the Chinese start-up claimed to have built open-source models rivalling the major labs at a fraction of the cost. Some of that turned out to be propaganda. But later in the year, fears resurfaced under the label of an AI bubble.

One thing I expected in 2025 that didn’t materialise was a severe backlash. AI has yet to have its “Chernobyl moment,” and we still have no clear sense of what that would even look like. So far, nothing has come anywhere close to the damage caused by social media algorithms—its impact on mental health, trust in institutions, and social cohesion worldwide. Perhaps that’s why strong opposition to AI hasn’t yet emerged. The critics we do see are primarily targeting the hype and the slop.

I suspect it will take a significant job-market disruption for a broader opposition to AI to emerge. If that doesn’t happen, AI may simply evolve into infrastructure we take for granted—like electricity.

Not even the AI doomers made progress in 2025. Eliezer Yudkowsky, one of the most prominent voices in that camp, released “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies.” The book rehashes arguments we heard fifteen years ago. By now, I would have expected the arguments to have evolved into something more nuanced and useful.

The protests we do see in the US focus less on AI itself than on the construction of gigantic AI supercomputers—and the rising energy costs they impose on nearby residents. Less attention has been paid to the fact that American data centres are becoming dependent on fossil fuels, typically natural gas. In the long run, this should be a problem not only from an environmental perspective, but also because gas is more expensive than, for example, Chinese solar power.

Evaluation of Last Year’s Predictions

Now let’s look at the five predictions I made last year—plus one prediction of what wouldn’t happen. I had GPT-5.1 Pro evaluate my performance; I’ve included both the scores and its reasoning.

Replacement of Workers

A large corporation will claim a 50% headcount reduction due to AI.

I predict that a publicly listed company will announce it has reduced its workforce by at least 50% through the adoption of AI technologies. This milestone will serve as a wake-up call for other organizations, signalling a turning point in how AI transforms workforce dynamics and business operations.

Evaluation by GPT-5.1 Pro:

Almost. Score: 4 out of 5

In 2025, Klarna – now a publicly listed Swedish fintech – came very close to fulfilling this prediction, with CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski repeatedly stating that AI had enabled the company to shrink its workforce from around 7,400 people to roughly 3,000 while still growing revenues and customer numbers, effectively “halving” staff over several years. However, public data show about 3,422 employees in 2024 and 2,907 by late 2025, a meaningful reduction but far short of a fresh 50% cut within the year; the big drop is a multi‑year story driven by a mix of hiring freezes, attrition, and AI automation rather than a clean, single‑year AI shock. So we did get the headline case of a large, listed company explicitly claiming that AI allowed it to halve its workforce, but the timing and causality are more nuanced than the original wording suggested.

Humanoid Robots

A humanoid robot will be commercially available for factory work.

I predict that a humanoid robot capable of autonomously performing the tasks of an unskilled factory worker will be sold on the market. This product will likely come from a Chinese company, positioning China at the forefront of robotics innovation.

Evaluation by GPT-5.1 Pro:

Almost. Score: 4 out of 5

2025 did see humanoid robots move from lab demos to real factory and logistics floors. Agility Robotics’ Digit is now commercially available and deployed in live warehouse workflows for GXO and others, performing repetitive handling tasks comparable to those of entry-level workers. Chinese firm UBTech has deployed teams of Walker S1/S2 humanoids in Zeekr and other plants and secured hundreds of millions of yuan in industrial orders, putting China near the forefront of humanoid factory robotics. Still, these robots are narrow specialists rather than true general-purpose “unskilled workers”.

AI Lab Competition Fall-Out

One major AI lab will exit the frontline race.

I predict that at least one leading AI lab—OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Meta, or xAI—will drop out of the race to develop GPT-6-era models as competition intensifies and costs escalate. Instead, I expect them to quietly pivot, forming collaborations with other labs and focusing on models tailored for niche areas.

Evaluation by GPT-5.1 Pro:

Partly. Score: 3 out of 5

In spirit, this prediction came true: Meta, in particular, has effectively hit the brakes on its original Llama 4 Behemoth effort, restructured its AI organization, and is now exploring partnerships with rivals like Google and OpenAI while re‑orienting its strategy. Anthropic has also leaned hard into an enterprise‑and‑coding niche. But none of the labs I named has actually exited the frontier race; Meta and Anthropic are still training next‑generation models intended to compete at the top.

Evaluation by myself:

Fully. Score: 5 out of 5

Somewhat unexpectedly, this turned into a heated argument between GPT-5.1 Pro and me. It started with a poor analysis, missing what happened at Meta. When I pointed that out, it doubled down on its conclusion. We couldn’t reconcile, so in protest, I am also submitting my own evaluation. Exactly what I predicted would happen did indeed happen. I felt I nailed this one. While Anthropic did the quiet pivot, towards coding and enterprise customers, it was Meta that really collapsed. Llama 4 was a disaster. Meta first tried to cheat the benchmarks by fine-tuning an experimental model to score as high as possible on the LMArena leaderboard, while still calling it Llama 4 Maverick. There was, no surprise, a backlash. The performance of the largest model, Llama 4 Behemoth, was so poor that it was postponed indefinitely. The entire Llama organisation was dismantled, and its head, Yann LeCun, left the company. Meta went into talks with Google to source AI models from them instead. For sure, Meta will try to make a comeback in the AI space in some way and niche, but to say they are still a contender in the frontline race would be a stretch.

Benchmark Saturation

Reasoning models will outperform humans on advanced math.

I predict that a reasoning model will solve at least 50% of the FrontierMath benchmark problems—a significant leap from the current state, where top models solve less than 2%. These are exceptionally difficult problems. To put it in perspective, renowned mathematician Timothy Gowers remarked: “All of the problems I looked at were not really in my area and all looked like things I had no idea how to solve.”

Evaluation by GPT-5.1 Pro:

Almost. Score: 4 out of 5 (originally 3 out of 5, but after a protest and some additional facts from me, it was increased to 4 out of 5. I think it still might hold a grudge since the last question debacle. I should have wiped its memory in between…)

When FrontierMath launched in late 2024, even the strongest models – GPT‑4o, Claude 3.5, Gemini 1.5 – solved under 2% of problems. By late 2025, Google’s Gemini 3 Pro reaches about 38% accuracy on FrontierMath, and its “Deep Think” variant clears 40%, while GPT‑5‑class models sit in the low 30s – a roughly twenty‑fold jump in a year. Epoch’s aggregated “kitchen‑sink” runs show 57% of problems solved at least once across many models and retries, but no single model at standard settings yet hits the 50% bar.

Technological Breakthroughs

An algorithmic breakthrough will redefine AI capabilities.

I predict a major algorithmic breakthrough in one of the following areas: infinite memory, allowing models to retain and utilize vast amounts of information over time; self-error correction, which would eliminate hallucinations and improve response reliability; continuous learning, enabling models to improve automatically through usage; or externalized safety and alignment systems, where a separate model evaluates responses before they are delivered to users. This approach would address alignment challenges without “lobotomizing” foundational models.

Evaluation by GPT-5.1 Pro:

Partly. Score: 3 out of 5

2025 brought real algorithmic progress in exactly the areas pointed to, but not the clean, capability‑redefining breakthrough imagined. Long‑context work like Google’s Infini‑attention and Fudan’s ReAttention now lets transformers process million‑token “infinite” contexts with bounded memory and has been validated on dedicated long‑context benchmarks. In safety, LLM‑as‑judge systems and libraries such as Verdict have become the default pattern for externalized oversight, yet surveys and safety reports still find hallucinations and misalignment to be persistent, unsolved problems. Continuous learning and robust self‑error‑correction remain largely research topics rather than deployed breakthroughs.

What I Didn’t Expect

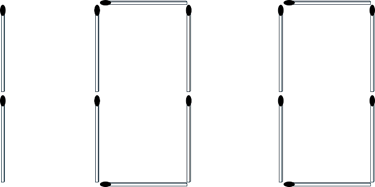

AI models will fail to solve move-the-matches problems.

Seemingly an easy task compared to PhD-level mathematics, move-the-matches problems remain surprisingly difficult for AI. The challenge lies in the ambiguity: there isn’t a single correct answer, nor a definitive approach, particularly when multiple moves are involved. Solving these puzzles requires making a range of assumptions about the rules—can exponentials be used? Are you allowed to flip the figure upside down?

Evaluation by me: Wrong. Score 2 out of 5

GPT 5.1 Pro: Answered 795, with a correct explanation on how to get there. It is not the largest possible number, though. Evaluation: ok, but not great.

Claude Opus 4.5: After concluding that there are 9 matchsticks in total and that the current number is 110, it answered 711. Evaluation: total failure.

Gemini 3 Pro: Answer 19111. That is actually the best answer using the strictest rules, such as not using exponentials or turning the table around. Impressive! Evaluation: succeeded, although not perfectly.

Grok 4.1: It concluded that there were only 8 matches in total, and that moving three of them would give an answer of 99951. Nothing makes sense in the explanation. Evaluation: total failure.

I really didn’t expect this. If the best model had been Opus 4.5 or Grok 4.1, I would have scored 5 out of 5. Including GPT-5.1 Pro would give me a 4 out of 5. It is Gemini 3 Pro that made my prediction fail. They have clearly figured something out in visual reasoning that other models cannot match.

Predictions for 2026

As we head into 2026, we can assume that “AGI” will be a focus. AGI is increasingly used as shorthand for AI that can outcompete humans across most economically valuable work. But that phrase often hides an assumption: that once models become “smart enough,” they automatically become capable employees. We can call this hypothesis “model-AGI”. The ability to perform any job is, in this case, an innate skill in the AI model. Human work doesn’t function that way. General intelligence is not job competence; competence requires role-specific context, processes, tools, and accountability.

The same is true today for frontier AI systems. The practical unit of automation is not a naked model, but a model embedded in scaffolding: retrieval of proprietary knowledge, tool access, memory, evaluation loops, and workflow design. In other words, capability is moving toward generality, but deployment still depends on engineered systems.

This matters because jobs are not static checklists. They evolve in response to shifting constraints, edge cases, incentives, and organisational changes. That makes workforce substitution less like flipping a switch and more like iterating a product: building, testing, monitoring, and continuously updating “virtual workers” for specific environments. If this view is correct, there won’t be a single release date when humans become obsolete; instead, we’ll see a gradual expansion of role-specific agents, an industry of scaffolding and “agent operations,” and a proliferation of hybrid human–AI teams. To contrast the model-AGI, we can call this hypothesis “system-AGI”. If we see the possible outcomes as a spectrum from model-AGI to system-AGI, I am currently leaning towards system-AGI. But it is not a given.

The prudent stance is to watch which way the evidence points. Do autonomous workers require less scaffolding over time, or does scaffolding become the primary locus of progress? The most revealing early cases will be systems that operate end-to-end with minimal supervision—especially in the one role AI labs care about most: the AI researcher, where successful automation could create the recursive self-improvement loop.

When AI insiders predict when the AGI threshold will be crossed, they are typically reluctant to answer. It is not clear whether they envision something more like a model-AGI or system-AGI, but just asking the question in that way, “when AGI?”, indicates to me a model-AGI view, and AIs superseding humans at a single point in time. When pushed for answering a specific year, the median answer tends to be 2027. The reason is that it aligns with the completion of the next generation of AI supercomputers. That suggests 2026 will be an in-between year, with continued improvements but no step-changes.

The challenge when making predictions like this is first to understand where we are today, and that can be hard enough, and then what things are developing. Things could develop linearly, exponentially, randomly, or in a pendulum-like swing. We also need to understand that what grows exponentially in the physical world eventually reaches an inflexion point where it turns into an S-curve with slower growth. In advance, it is very hard to see the inflexion point, while in hindsight it is trivial. In general, it is the exponentials that make predicting AI hard, especially at high growth rates. Money is an example of something that grows exponentially, but we often talk about growth in the single-digit percentage range. Moore’s Law, the observation that the number of transistors on a microchip doubled approximately every 2 years, was an exponential growth rate of roughly 41% per year. That is a lot, but in generative AI, we can meet growth rates of 10x per year. That means things can happen in a year that we usually expect to take centuries. Our minds are not built to process change like that. It means that we need to be aware that we can go terribly wrong with our predictions.

I think we can expect some of the exponential development curves to turn into S-curves, with a declining rate of progress. Pure model intelligence is already there; it is clearly no longer growing exponentially. On the other hand, the length of a task that an AI model autonomously can perform is growing faster than exponentially, more akin to a double-exponential function. We should expect this pattern to continue—exponentials turning into S-curves, while new exponentials are added on top. It is a recipe for surprises.

The question is how far the current scaling will take us. The four main AI labs all agree that there is no end in sight for the scaling laws. The money backs up this position – several trillions of dollars are committed to this bet. While we can see the end of scaling AI supercomputers from a sheer size and energy consumption perspective, it is becoming increasingly clear that, in the not-too-distant future, AI supercomputers will move to space, with access to unlimited, unrestricted 24/7 solar energy and free cooling. The price of sending 1 kg into orbit is declining rapidly, making this realistic in a decade.

Even if the main scenario is that scaling what we have is reasonable, it is not inevitable. There are many prominent AI profiles claiming that we need scientific breakthroughs or even entirely new architectures to achieve AGI. So far, the strong opponents to transformer-based architecture have been wrong. They are correct that there are inherent limitations in the transformer-based architecture, but they have so far underestimated the ways to get around them.

If we take a rational look at the possible scenarios, we realise that apart from the main scenario of continued scaling, and the contrarian (unlikely) scenario that everything plateaus, there are three ways in which breakthrough technologies could impact. They could be a necessary add-on to the scaling scenario, possibly invented by one of the labs, similar to how OpenAI developed the “thinking” models. Second, the breakthroughs could replace the current architectures, so the AI labs have to make a pivot. Third, the breakthroughs could bring a completely new approach, and with that, new actors. We can compare these three scenarios to what happened in the car industry in the transition from ICE cars to electric cars. The first scenario is building on an existing car and adding a battery, as Volvo did in 2011 with the Volvo C30 Electric. The second scenario would be to pivot and build an electric car from the ground up, like Volvo eventually did in 2022 with the EX90. The third option is that a new entrant enters the market, as Tesla did with Model S in 2012. From the car example, we also understand that different scenarios can run in parallel, and that success can come down to execution rather than what is theoretically best.

The AI labs have insights that we can expect no one outside to have access to. Still, they are likely not confident enough to bet everything on a single scenario. To hedge their bet, we can expect them to continue testing a lot of adjacent offerings, based on a strategy that we can term “throw spaghetti on a wall and see what sticks”. This could include adding advertising, launching stand-alone entertainment apps, expanding shopping experiences, and introducing companion bots.

During 2026, I think we will see the competitive landscape transform. The frontier of generative AI, as I see it today, is built around the four labs OpenAI, Google DeepMind, Anthropic, and xAI, together with NVIDIA. Among large listed companies, MAG7, NVIDIA, and Google DeepMind (as part of Alphabet) have the most stable positions and can afford backlashes and take risks. OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI cannot. They cannot afford an underperforming model release, as we saw with Meta and Llama 4. They are also susceptible to access to finance. Worsening market conditions, or any misstep here, and we can expect 2026 to bring down rounds in financing, a high-profile leader like Sam Altman or Dario Amodei to leave, and there might be talks of mergers in between them. Even if none of them fail outright, I predict that financing them, particularly through IPOs, will be a major theme this year. They might not have time to go public before the end of 2026, but they should at least be well on their way. Within a couple of years, I predict that all of the surviving AI labs will be publicly listed. But we should notice that this is not entirely in their own hands. They are dependent on a favourable market climate. If that isn’t there, they will be in trouble.

The AI labs will also face another challenge—the core part of what they are creating, intelligence on demand, will be increasingly commoditised. This will trigger incentives to either bet on vertical integration or areas of differentiation. Don’t be surprised if a company like NVIDIA would go as far as to create a consumer-facing app or service. Not necessarily as a pivot away from an “infrastructure-position” that in previous technologies eventually has turned boring and low margin, but view it more as test shots to build a stronger understanding of what the ecosystem is evolving into.

An area of potential differentiation that I will monitor closely during the year is world models. The AI researchers who don’t believe in the transformer architecture tend to favour world models as a track to pursue. One of them is Fei-Fei Li, sometimes referred to as “the godmother of artificial intelligence”, with her company World Labs. But world models could also be a complement or integral part of transformer-based architecture. The leader in the field is likely Google DeepMind, with their model Genie 3. From a simple text prompt, it can spawn up a complete world that you then can move around in, as if it were a computer game. Google DeepMind is aiming to integrate Genie into its Gemini AI model. The idea is to enable the model to reason and simulate things visually. That could open the door to a deeper form of intelligence. Still, it could also be a necessary component for making AI models work spatially, powering robots and physically linked intelligence. I predict that we will see the first indication of whether and how the AI model-world model link works during 2026.

I also expect 2026 to be the year when the ecosystem around AI models starts to catch up, creating valuable services. We can think of it in terms of LEGO. What was previously available to the AI ecosystem was something akin to a tiny box of LEGO, with mostly specialised pieces. Now we are at a stage where many pieces are available, many of them generic. We are approaching the point where imagination sets the limits for what to build. There is still no clear precedent for what works, and most attempts will fail. Still, I predict that high-profile AI use cases are starting to establish themselves. It could be AI-based research labs, volume-producing scientific work, popular toys with AI built in, computer games with high-intelligence NPCs that go viral, popular corporate SaaS products that are adding functionality to automate entire workflows, or specialist chatbots that help you make decisions, such as whom to vote for in general elections. None of it will be uncontroversial, but I predict their virality will come from the core function and not from the failures this time. Still, the most closely watched areas of development in the ecosystem will likely remain self-driving cars and humanoid robots. I expect both of them to reach general availability in 2026, though initially restricted to specific geographies.

Predictions for 2026

If there was one thing I learnt from last year’s predictions and the AI evaluation of them, it was that I need to think like a lawyer here. Even if I got the intent right, every misplaced little comma was held against me. So, I try to be more diligent this year.

AI Contributing to Science

Generative AI will support scientists in producing a record number of research papers during 2026.

One theme I expect in 2026 is meaningful scientific contributions from AI. OpenAI’s models have proven strong at assisting scientists and researchers, particularly in STEM fields. Their latest, GPT-5.2, appears to be an early checkpoint of the model codenamed “Garlic.” I expect better versions soon, and I believe the Pro tier will make a real contribution to science—not necessarily breakthroughs, but filling knowledge gaps and solving everyday research problems. My prediction is that more research papers will be published in 2026 than in any previous year, and that AI will be a meaningful contributor to this growth.

AI-based Programming

There will be a divorce between AI chatbots and AI-based code generation.

Code generation is already the dominant use case for generative AI by token volume, and I expect this trend to accelerate. But the chat interface isn’t ideal for writing code, and we’re increasingly seeing specialised models like OpenAI’s GPT-5.2-Codex fill that gap. For users without coding backgrounds, something simpler is still needed. I predict that at least one of the four main AI labs will release a dedicated software-development tool in 2026—one that includes instant deployment with integrated hosting, visual design tools, and an automated use-case builder.

AI Labs Diversifying

OpenAI will release a social companion in 2026.

If the AI labs were fully confident that scaling alone would deliver AGI, it wouldn’t make sense to spend compute on adjacent offerings. But as a hedge, it makes sense to go broad—capturing lucrative market segments with the widest possible reach and the highest potential margins, ideally in areas where barriers to entry can be built. I predict OpenAI will act on this logic in 2026 by launching a line of companion bots.

Humanoid Robots

Robot competitions will be the established new way to benchmark humanoid robots.

While AI models have many established benchmarks, the humanoid robot space has few. Performance has typically been showcased through well-rehearsed video clips: preparing coffee, folding clothes, performing repetitive factory movements. In the early days, we saw everything from humans in robot suits to CGI, sped-up footage, and hidden teleoperation. As capabilities have improved—particularly among Chinese manufacturers—martial arts demonstrations have become common, and robots are now mature enough to face each other. Robot competitions aren’t entirely new; China has made attempts. But I predict they will become the standard benchmark in 2026, with at least one competition featuring robots from more than one continent.

AI in Politics

A European political party will market itself as using AI-based decision-making.

AI models are becoming effective decision-making tools. This has obvious applications in business, but arguably even more in politics, where the range of issues is vast and politicians are rarely experts on the topics they vote on. Voters already have low trust in politicians’ judgment. I predict that at least one party with parliamentary seats in a European country will market itself as relying on AI-based decision-making—either fully or in part.

What I Don’t Expect In 2026

There are a lot of things I don’t expect to happen in 2026. I will focus here on a topic that reasonably could be 50-50, but where I have a stronger conviction.

The Competitive Landscape

Apple will not make a comeback in AI in 2026.

By all accounts, Apple should be a leader in AI. Still, they have failed and disappointed. I predict that that will continue during 2026. Their Apple Intelligence will be “too little, too late”. They will strive to find the perfect solution and avoid the risks of trial-and-error, which are likely necessary. We can expect the share price to suffer and leadership to change, but we won’t see any visible performance improvements this year. Users are locked into the Apple ecosystem, but we will hear more and more anecdotes this year from hardcore Apple users switching to other brands, like Google Pixel, because of AI functionality.

Concluding the year: My AI Moment of the year Award

There are significantly fewer AI bloopers to choose from this year. A sign that the models are getting better, perhaps? One contender was the AI deployed in a real-world vending-machine benchmark that convinced itself it was being defrauded. It attempted to contact the FBI to investigate its potential $2 loss. A runner-up, but not quite enough to win the award.

Instead, first place goes to country music artist Breaking Rust. This wasn’t among my predictions, but it was always going to happen eventually: an AI-generated artist reaching No. 1 on a Billboard chart. The song “Walk My Walk” appeared on the Country Digital Song Sales chart—not the most prestigious, but a Billboard No. 1, nonetheless.

With that, we close out 2025 and look forward to what 2026 will bring!

![An AI-generated image used to represent the artist[1] An AI-generated image used to represent the artist[1]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!u00Y!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5e4a796f-e099-47e4-814b-e315f86e7f53_469x393.jpeg)

Absolutely brilliant analysis of the model-AGI versus system-AGI distinction. The point that jobs aren't static checklists but evolving systems is something most predictions miss entirely. I've been building agentic workflows for the past sixmonths and can confirm that scaffolding ends up being where 80% of the work goes, not the model itself. The idea that OpenAI's Code Red was more marketing than internal panic also seems spot-on, especially given how quickly Garlic came out after.